How do you write a poetry of war? And, by that I mean, the end of war?

The First World War produced the famous British “war poets,” including Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon. At school we learned their inconsolable lament for young manhood cut down in the gobbling carnage of trench war. The trenches pressed huge numbers of human beings together, both as comrades and enemies. The suffering of all those human beings could not be ignored, so there was inevitably a poetry, one essentially of the end of war

But now everything is digital, smart, hypersonic, nuclear, without any time to see or think. What can be seen is in fact only another digital product, the media which surrounds us 24/7 and takes on a life of its own. How can you trust what is presented to you? Even if it’s true and factual its enormous immediacy in our sitting rooms overwhelms our ability to meditate humanly, deeply and clearly. Not even Homer, I think, could have written about modern war—because modern media does not allow the human space for reflection and art. Instead it carries us along on the relentless tide of war itself, and indeed of total war.

Which brings us to the teaching of the gospel. The gospel is the only resource that can restore primacy to the human in the context of modern war. It creates its own, vital distance. “You will hear of wars and rumors of wars, but see to it that you are not alarmed. These things must happen, but the end is still to come. Nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom . . . All these are but the beginning of birth pangs.” (Matt 24:6-8)

The gospel tells us not to trust to war, and its media, for the ultimate meanings of humanity. This is an absolutely essential teaching for our modern age with its terminal despairing perceptions. This is not to underestimate the destructive forces in the hands of human beings, and the possibility of their unleashing them, and indeed the fact of their already being unleashed. But what it does tell us is that the gospel places another transforming dimension in human affairs, one which is not going to be canceled out by war, but in fact grows step by step with the lethal threats of violent meaning.

This is the language of the gospel itself and not a logical, mechanical deduction from history or anthropology. It is a matter of what I might call aionology (pronounce aye-on-ology).

Oh, no, not another “ology” word for Christians to learn, I hear you say! But, yes, I’m afraid it’s so!

I consider aionology essential and urgent for our time. We are generally used to what theology calls “eschatology,” i.e. the end times brought by Christ at his appearing, as a definitive line drawn between this world and the next of “eternal life.” But in the New Testament Jesus has recourse to the concept of “the age” (aion), rather than eternity, something that is consistently misrepresented in the translations. “Aion” or “age” in its literal sense does not abolish time, as eternity does. It basically tells us that there is a radical break expected between the present age and the age to come, meaning that the cosmos is changed radically, but it is still the same essential time-filled sphere of human existence as before.

Sometimes in the New Testament it is almost impossible to avoid the correct translation. A good example is in Luke chapter sixteen and the parable of the dishonest manager. At verse eight the “master complimented the unrighteous manager because he had acted shrewdly; for the sons of this age (aion) are more shrewd in relation to their own kind than the sons of light” (New American Standard Bible). The passage then goes on to tell us to “make friends for yourselves from the Mammon of unrighteousness so that when it gives out they may welcome you into the tents of the Age (aion)” (David Bentley Hart). The clear implication is that there is the present age, and then there is another one, appropriate for a people of light, where they will be welcomed and live in something this-worldly as tents!

The same (“of the age” or plural “for ages”) meaning of aion can be read in the other places where it appears, and it tells us again and again that the continuity of time is not broken by an alien Platonic eternity. And there are other hints in the New Testament that Jesus foresaw a radical renewal of creation rather than a negation of the material realm (viz. Matt 19:28, and Acts 3:21). It does not mean that time will be experienced as it is now—with its subjugation to death, insecurity, violence, war. Rather, precisely, its experience will be liberated from these things, yet still in an enduring material, temporal reality!

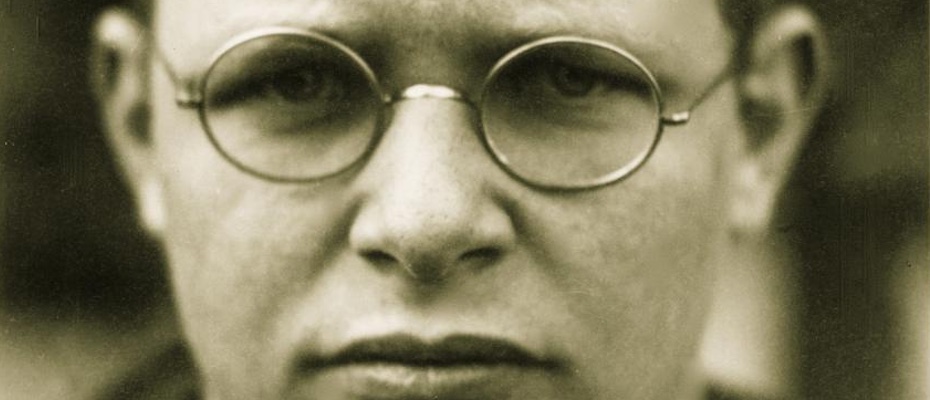

This is the horizon of aionology. It was a horizon embraced by the German theologian, Bonhoeffer, but perhaps in an even more radical way. For Bonhoeffer the world had reached a point where it operated without “the working hypothesis” of God. It seems to get along fine on its own without God. But rather than double down on trying to convince people of God, the role of the Christian becomes the same as that of God—to suffer in the world, and with the world, as it struggles to be the world.

I discovered later, and I’m still discovering right up to this moment, that it is only by living completely in this world that one learns to have faith… By this-worldliness I mean living unreservedly in life’s duties, problems, successes and failures, experiences and perplexities. In doing so, we throw ourselves completely into the arms of God, taking seriously, not our own sufferings, but those of God in the world — watching with Christ in Gethsemane. That, I think, is faith; that is metanoia; and that is how one becomes a human being and a Christian. (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters from Prison.)

The purpose of this co-suffering is far from masochistic; it is creative and transformative. If God is in the depths of the world in this way, and Christians are with God, it means that the world is being called from its depths to the end of violence, the end of war, the end of hatred . . . to radical change of heart.

It is this that provides the meaning of war for Christians, the poetry of the end of war. Aionology is the meaning of God as a deep undertow, a reversal of everything, and something already going on. It is the melting of the ice caps in a spiritual sense, leaving an ecology where God strips the world of its violent meanings, where the present triumph of generative murder is completely overcome and undone. The material realm is already spiritual. It is itself spirituality presently unrecognized, but destined for final full revelation.

Even so a poetry of the end of war arises by virtue of the age, in which we live, the age given by the gospel.

Note. Initial artwork by Patty Halbeck

Something about your reflection on the Age brought to mind these well-known lines from Arnold’s “Dover Beach” …

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.