There is a truth of love which overtakes the heart.

As if someone slid back a panel deep in the basement of the soul, revealing a dark stream which has not seen the light for a billion years. The limpid dark water of divine love. Undertow to the universe.

Girard says there is an originary murder at the basis of humanity.

The location, the spot, the place where the murder occurs—like all associations, in sound, equipment, time—becomes sacred. There is a sense of power, fear, awe about them—the phenomenon of the sacred.

Later, when humans turn to building, it occurs to them spontaneously to make the foundation stone of a building or wall sacred—by carrying out a foundation murder or sacrifice. That way it will have numinous strength. So, we find the countless foundation sacrifices of human culture: the bones of birds. animals, children, adults, are found beneath walls, towers, corners, hearths, doorsills. . . . from India to Mexico, from Saxon England to North Africa.

Rozafa Castle Foundation Sacrifice

The stunning visual of Rozafa castle in Albania spells out the story in one. The legend tells of three laborers building the castle wall. Despite their best efforts each night the wall would collapse; a wise man counseled them that only the sacrifice of one of the builders’ wives, mortared within the wall, would keep it strong; the wife of the youngest (of course) was chosen and she accepted her fate, but on one condition; one eye, one breast, one leg had to be left exposed in order to suckle and dandle her infant; the rest could be walled up. And so it is, the castle stands strong to this day. (The story was told to me in class by an Albanian student, while I was teaching on the foundational victim. The whole legend is in fact a classic, culturally Christian foundation story—the victim is half-revealed in a factual sense, half-revered in a superstitious sense, a kind of half-effective double transference.)

The foundation stone is sacred by virtue of the killing, by virtue of the blood, but it is the stone which becomes important for humans. The wall must stay strong. The city must endure. It is the stone which creates enclaves and houses, castles and civilizations. It is almost inconceivable for human beings to make things without the stone. The stone absorbs the life and blood of the victim. These things remain hidden in the stone. The stone stands forth strong and noble in its own right

Except, that is, until the Lamb.

The Lamb of Revelation appears in the world “as one who was slaughtered,” making plain the murdered creature by which the stone is made strong. The Lamb refuses to pour out its blood for the sake of the stone. Instead it reveals the truth of spilled blood, in its case given for and as love, but, because it is revelation, in the same moment it makes the stone weak and unstable.

This is not a happy situation for the world, and by orders of intensity. Its most treasured, original artifact—the stone—is subverted in its essential being and function. The modern world is rendered unstable at its core. You could say a nuclear reactor is simply the modern technological realization of the instability at the core of our human-spiritual condition.

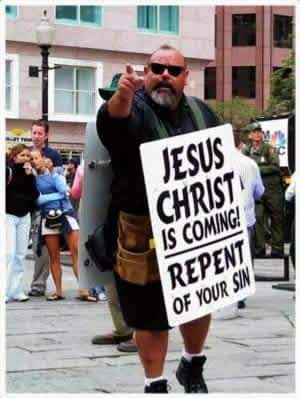

But, not to worry, we still have fundamentalist Christianity! Fundamentalists repeat language of the blood, but it’s the stone they’re really interested in. By dint of a thousand years of atonement theology they have turned the thing upside down. Rather than revelation, they see the blood of the Lamb as warranting and supporting the stone. Because the blood is offered in compensation to a wrathful God, the figure of “God” becomes the apex agent of violence, a meaning that enshrines and exceeds all the violence of the world. God becomes the stone in the sky about to fall on us. Some indeed might readily admit this, because in their minds it seems like the honor and respect due to God (God can do what God likes), but it is just another version of the stone. The symbolism or conceptual place where the violent way of the world comes together most powerfully is always the stone, the foundation of the world.

Liberal thinking doesn’t think this way. In fact, it doesn’t mind being considered irreligious: rather it takes the side of the victim and that is where its righteousness lies. Its approach seems, by definition, to be free of blood, and so it is necessarily non-foundational and righteous. But the moment it gathers in a crowd (including virtual) to stake out its position, to accuse, condemn and cancel the victim-maker, we are inevitably producing the stone on that side too. This is because humanity has not changed its core relation with violence, its generative anthropology, its root way of being. Without this radical change the intensity of liberalism’s desire to found the world on principles of justice and inclusivity will only produce a new round of the same old sacred. More subtle and diffuse perhaps, and enshrined above all in language—in staking out territory in symbolic, semiotic terms—it is nevertheless just as ferociously constructed of “stones” as any fortress. The “right side of history” can so easily mean a new sacred space, where stones are thrown, and the foundation stone laid down all over again.

The blood of the Lamb undermines all foundation stones, crying out only for nonviolence, mercy, forgiveness, and love. That is why it is so endlessly disruptive. Fundamentalist Christians are the reaction of violent history, seeking to restore the foundation stone within the very message that dissolves it. But because of the very nature of the blood of the Lamb, revealing the victim, fundamentalism is always itself destabilized. Proof of this is its central need for its own form of victim language. Abortion is right-wing Christianity’s preferred and only victim. The fetus in the womb appears separate from the conflicts and violence of adult human mimesis, so to insist on protecting this life, while forgetting all other issues of life under threat, makes for a privileged language that stops short of all other killings. But all along right-wing Christianity’s insistence on this issue shows that it shares a common worldview of the victim—while all the time seeking desperately to refound society on the stone covered with its blood. This kind of Christianity is inherently conflicted, angered, angry and unhappy, by virtue of its own core symbolism and meaning.

The bible ends with the book of Revelation, and the book of Revelation ends with a vision of the heavenly city coming to earth. The city is the city of the Lamb, but it comes “from heaven” and therefore is not founded on the originary violence at the root of our humanity. The blood of the lamb is a totally different blood, communicating only endless forgiveness and love. The New Jerusalem is made up of a vast number of stones, described in luminous detail in chapter twenty one . The city itself can itself be viewed as one huge stone, a perfect cube twelve thousand stadia long at each equal edge. But, again, this is not the stone of human culture. It is a completely different kind of stone, shot through with light. There is no violence or falsehood in the city, thus requiring no foundation to keep things in order. Only the totally nonviolent meaning of the blood of the Lamb, recreating human relation as such, is able to do this.

By and large throughout its history Christianity has missed this recreating relation in the blood of the Lamb. But our global humanity is today at a moment of crisis when it desperately needs it. How can the world founded on the stone of violence experience the nonviolent stone of the Heavenly Jerusalem? Every Christian carries it within her! It is a kind of half-light or dawn of the Lamb brought into the world by every breath of the Christian. A Christian is defined by relation with the Lamb, the relation of the Lamb, in forgiveness and compassion. The Christian is this relation.

When I slid back that panel in the basement of the soul I think what I saw there is really the energy of the Lamb coursing through history, through the universe. It is unstoppable, unquenchable, a way of being in its own right, unbeholden to mimesis either right or left. It is at the root of all things, in these latter days manifest in the world by proclamation of the Lamb.

What other “killings” are ignored by rightwing fundamentalists? Social justice issues?

War, prisons, guns, poverty, racism . . . the list goes on. But the Lamb is bringing all things to light!