The church rises up, a sudden eruption of art and meaning on a sun-beaten coastal plain. The place used to be abutting a strategic harbor next to the sea until the shoreline moved away. Now its sudden presence in the middle of nowhere reinforces the feeling of a wonderful alien interruption of standard human affairs. Like a beautiful mother-ship set down to invite travelers to journey to another world.

In literal terms the building should be understood as the Christian re-imagining of the standard imperial urban “basilica,” the roofed public space for the conduct of Roman business and law. Because Christian gatherings were not the private sacral space of the temple, reserved for the god and the priests, but rather a communal assembly and event, these big buildings made an ideal template. As the Christian movement emerged from persecution and hiding it imitated the secular buildings where citizens came together freely for ordinary human affairs. First lesson, therefore: a “basilica” is essentially a secular space, something ordinary, human, communal, down-to-earth.

Basilica of San Apollinare in Classe

Second thing: some context. This church, along with others in the neighboring Adriatic city of Ravenna, reflect the political and military success of Justinian I, the Byzantine Roman Emperor lately taking power back from barbarian conquerors of Italy. Justinian saw it as his job to ensure the conformity of everyone in his empire to orthodox Christian faith, meaning, essentially, the doctrine of the two natures of Christ, fully divine, fully human. This is a far cry from Christian faith as a persecuted and despised minority religion, which was the case just a little over two centuries prior. But imperial politics are not entirely the point here.

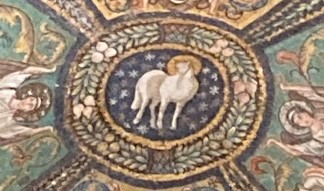

What is the point is the wonder of a vision which saw human existence fully caught up in divine existence. While the emperor and his violence knew themselves supported and endorsed by Christian institutional religion, the core vision of this splendid church by the sea is of a humanity completely transformed by communication of nonviolent divinity. In the glorious crowning image of the apse there is no other-worldly procession of saints and martyrs, nor any hint of the emperor or his court, only a panorama of sheep in a land of peace! Whoever conceived this majestic mosaic figured humanity’s identification with the divine not in terms of a disembodied spiritual other-world but an earth turned entirely to its own deepest possibilities of love, nonviolence and life. The doctrine of the two natures and one person was for this visionary artist a human world set free from harm. The divine conjoined to the human meant the communication of divine nonviolence to every relational being, and therewith the creation of the truly human and divine person.

So, a third thing: the beauty of sheep! What are these animals raised to the roof of an imperial building where before it was likely Winged Victory with horses and a war chariot looking down? These are the defenseless, the meek, the disarmed, the humble, the creatures at the wrong end of humanity’s systems of force and blood-letting. But now somehow they are in a land made just for them, a land of tranquility and plenty, with not a sword in sight! It is alternative human space. It is the public building, the basilica, made for the conduct of human affairs by active means other than violence.

San Apollinare Apse

As you enter the main building the wide welcoming sweep of a foot-worn marble floor underscores there are no seats or pews where people sit to become passive recipients of doctrine. There is only a standing space of human interaction and proximity. The gleam of the floor naturally invites you in, and then lifts up the head to where the light pours through the windows above. There is a great deal of light. The pillars of flowing marble also lead upward and onward, toward the luminous final vision of the triumphal apse. And there the wonder reveals itself. It is here that this public space declares its most profound and generative meaning. It is not simply a concourse of citizens, but a gathering of the human species, onetime victims of their own chronic violence, now transformed into something dramatically and miraculously new. The glowing color of the apse is green, the kind of green of a field or wood at the turn from spring to summer, fresh, warm, touchable, edible, endless. And the dominant figure or symbol within the intense wash of green is the sheep.

Sheep are everywhere, two sets of twelve, and three in the middle. Below they surround the (first or second century) martyr-bishop Apollinaris in the figure of the Good Shepherd, above they stream from images of the New Jerusalem set in the corners of the vertical wall. The iconography bends the world inside out, with the standard victim of human slaughter become now the symbol of humanity set free from violence, in a space of sensate peace and pleasure. How is this perceptual-spatial miracle possible? It can only be by means of a twisting around of normally imagined space, where the victim is systematically not figured, where human business is conducted as usual. Or, if the victim is figured, it is in the shadow of triumphant violence. Here instead the archetypal object of killing, the sheep, becomes the triumphant master image, radiating its inherent nonretaliation as the orchestrating theme of space itself. It is a miracle of art and figuration, but it is born not from artistic imagination as such but from something that has occurred in the public space of citizens below. Thus, the basilica becomes not a place of the king and his many weapons, but of the king’s many vanquished citizens—and possibly the king too—now willingly embracing the loss of weaponry. The icon of the sheep as the brilliant central motif of this space turns the basilica upside down, making it light as air, floating with its inhabitants, like astronauts, in a new order of gravity. The Roman public building has gone from law court, institution of human violence, to an outer/inner space of grace, the transformed dimensions of nonviolent human being. Centuries of Christianity as business-as-usual has masked this transformation catastrophically, but now little by little its deep revolution in human space is being recognized for what it is, in and through spontaneous eruptions like this basilica on the shores of the Adriatic.