I was ordained in 1973, and resigned the priesthood in 1984.

In the Roman Catholic church priesthood is a lifelong commitment, including its core social marker, lifelong celibacy. To jump ship and get married is not even technically possible according to Canon Law (you can’t escape a solemn vow), let alone something viewed as an honorable course of action.

It is legally possible to be “returned to the lay state”–on the basis it was all a total mistake in the first place–but my own petition for dispensation disappeared in some clerical desk-drawer around 1986, and I never felt inclined to try again. I preferred to remain in the odd clinical condition which is my true and real vocation.

My mother was mentally ill—borderline psychotic, for sure. Her presenting symptoms  were chronic underlying depression, triggered by postpartum crisis. But on its own this does not account for her rages which were the real pathology. Her anger was directed mostly at my father. He was not only personally culpable (for whatever grave sin she found him in), but he served as a stand-in for the general evil of England responsible for millennial Irish grievance. Although my father bore the brunt of my mother’s blitzkrieg, it was also capable of wiping the whole house clean of air and life more terminally than any atom bomb. It was not surprising I developed chronic asthma trying to vent the firestorm. But it was not enough. It could not remake a world after the apocalypse. For that only priesthood would do.

were chronic underlying depression, triggered by postpartum crisis. But on its own this does not account for her rages which were the real pathology. Her anger was directed mostly at my father. He was not only personally culpable (for whatever grave sin she found him in), but he served as a stand-in for the general evil of England responsible for millennial Irish grievance. Although my father bore the brunt of my mother’s blitzkrieg, it was also capable of wiping the whole house clean of air and life more terminally than any atom bomb. It was not surprising I developed chronic asthma trying to vent the firestorm. But it was not enough. It could not remake a world after the apocalypse. For that only priesthood would do.

From a very early age “the priest” was the only figure of manhood put before me of any value. A paragon of virtue, truth, power, beauty, humanity. At the same time, I had my own strange, personal connection to things of the spirit, a powerful, individual relation to the man from Nazareth which in fact stood outside of the architecture of the Roman church. I also learned to pray, a constant inner exercise of breath, reaching out for life beyond the gutted atmosphere of my personal spaceship drifting on the far side of the moon.

Back then, however, spirituality and the Catholic church were impossibly intertwined and created a recipe that could only enhance the madness of my soul and social situation.

When I finally quit the priesthood—motivated in large part by the healing touch and  liberating teaching of the man from Nazareth—I was able to distinguish between the meaning and impact of the Christian scriptures and tradition, and the self-serving historical structures of the church. Nevertheless, there was one thing that would not change. I could remove the the man from the madness, but I could not remove the madness from the man.

liberating teaching of the man from Nazareth—I was able to distinguish between the meaning and impact of the Christian scriptures and tradition, and the self-serving historical structures of the church. Nevertheless, there was one thing that would not change. I could remove the the man from the madness, but I could not remove the madness from the man.

I had learned more thoroughly than a musical prodigy learns the piano. I exercised my personal priesthood from the age of six or seven forward, ministering to and mediating my mother’s depression and anger. There will be some other place where I tell the full story, but for now it’s simply a fact that I am specialist in any person who stands in the outside space, beyond the “normal” mores and values of the world. Psychosis—in one social form or other—is my wheelhouse.

Leaving the official priesthood was a necessary option for my sanity, for real connection to the world. If I had not done it there’s no doubt, I would have driven some group of people seriously nuts, or gone entirely nuts myself … or both. As it is, I have a wife and children who keep me grounded, and coming to the United States enabled me to breathe air whose atoms have not been ripped from the earth at the first dawning of conscious life. My mother responded to my bid for sanity by effectively never speaking to me again. I was to be forever outside her comforting mania.

All the same, as I say, I retain a priesthood of the borderlines. And at this point I have no desire to change. Madness comes one person at a time. If you go into a psychiatric hospital, there may be fifty patients, but each is largely lost in their own world. It’s difficult to conceive of a “church” of the mad. So it is that the ministry that I have learned at my mother’s knee always seems to be to the scattered, marginal few.

But. But.

The world is now in a place where what is “normal” is more and more deranged, both in  the breakdown of nature, and in the constantly reinforced twittermania of competing voices, such that “truth” is evaporated in the internet media. Madness is becoming a way of being, and in a world of the culturally insane the ordinarily crazy may actually have a new wisdom to impart. A priesthood of madness may be the path on which we meet the man from Nazareth more surely than down the aisle of any classically proportioned cathedral. After all, what is it that drives people insane, and what is that heals them? Is it not always some form of violence that pushes them over the edge, and is it not the touch of divine nonviolence which heals?

the breakdown of nature, and in the constantly reinforced twittermania of competing voices, such that “truth” is evaporated in the internet media. Madness is becoming a way of being, and in a world of the culturally insane the ordinarily crazy may actually have a new wisdom to impart. A priesthood of madness may be the path on which we meet the man from Nazareth more surely than down the aisle of any classically proportioned cathedral. After all, what is it that drives people insane, and what is that heals them? Is it not always some form of violence that pushes them over the edge, and is it not the touch of divine nonviolence which heals?

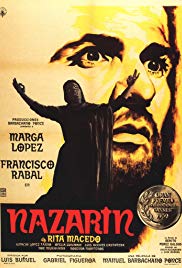

Any priesthood today worth its salt has to be a priesthood of madness. (I think of Luis Buñuel film, Nazarín, where the priest’s constant literal practice of the gospel makes him seem crazy and a failure. But there is always a deep ambiguity and the power of the images overcomes the harsh details of the plot. It is the images (the signs) of love and compassion that endure.

Thank you Tony. This helps me understand you better. I will be eternally grateful for the help you gave in my journey toward health. I know that I don’t fit anyplace conventionally and I am O.K. with that.

Thank you, Tom. Your friendship is huge for me. I think all us “oddballs” somehow already recognize each other at a distance! Tony

Tony … this (Episcopal) priest is grateful to you and to God for leaving your lasting ‘mad mark’ on me as a teacher and guide to Girard’s thought at Bexley Hall Seminary — and for continuing to shape my ministry today with the honesty of confessions like this one … Richard+

Thank you, Richard. I remember you very well, sitting at the opposite end of the seminar table, with your twinkling open-to-possibility blue eyes! It’s remarkable to me those classes continue to have impact on what might be called established church. But then not really. These days, I think the transformative gospel is more and more the language of every faithful Christian (like you!)