(Warning: thematic spoilers.)

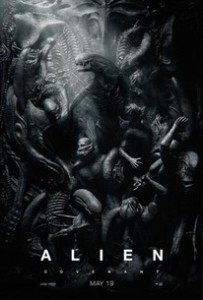

Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant (2017) is a meditation on actual human meaning painted across the aching canvas of outer space and set off by the placenta-toned hues of chest-bursting Xenomorphs, the undisputed cinema icons of human mimesis, misery and violence.

The titular spaceship, “The Covenant,” is the painting’s golden frame, a beautiful artefact, gliding effortlessly across the stars like the bone-weapon flung triumphantly into the sky all those years ago in Stanley Kubrick’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. The craft carries 2000 chosen people plus embryos, pilgrim colonists, to a new home on a distant planet. But with whom do they make the covenant?

The film begins with a 2001: A Space Odyssey style conversation between computer intelligence and its human master. It is set in the exquisite calm of high culture, a white room with modernist picture window looking out on wilderness landscape, and masterpieces scattered around like a billionaire’s eat-your-heart-out collection, Carlo Bugatti throne, Steinway Grand Piano, Piero Della Francesca’s Nativity, an image of Michelangelo’s David, and, for audio, Wagner’s Entry of the Gods. The scene connects to the movie’s prequel, Prometheus (2012): it fills in that movie’s backstory of Peter Weyland, the said billionaire, funding a quest in space to find the origins of human existence, including his own selfish pursuit of immortality. Here he is talking to the android who is his creation and will help him in the quest. But it is not Weyland who is the most important figure in the scene; rather it is the creation who proceeds to name himself triumphantly after Michelangelo’s biblical David and then play the Nazi-favorite Wagner piece. He resents his role as servant. In the flicker of an eye we can see that he does not want to pour Weyland’s tea!

The Covenant sails on its light-speed journey with its covenant god watching over it. The constant connection with and contrast to the Judaeo-Christian narrative tells us that, along with the CGI thrills, there is a theological imagination at work. There is the Nativity artwork at the beginning, the eponym of the spacecraft, multiple (if somewhat incoherent) references to faith and belief, as well as several subtle nods to the gospel story.

But the god at work is not a biblical god of justice or peace. As imaged so powerfully by the Xenomorphs it is one of ferocious rivalry. In fact it is David who little by little emerges as Lucifer, a pure rival to his creator.

He explicitly quotes Milton’s Paradise Lost, “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven” and talks eloquently of his superiority.

He claims precedence over humans because he knows his creator, and they do not, plus he can live indefinitely, and they cannot. But, at the same time, David has an intense case of creator envy. He longs to produce something as wonderful as poetry or music. He has fashioned primitive wind instruments for himself, but we cannot be sure whether what he plays is not plagiarised from human composers. However, what he really can do is create killing machines. Without giving too much away, we see that he does not hesitate to destroy, and on a metaphysical level, in his quest for superiority.

However, as you watch this drama unfold you begin to think that it is the very fact that humans do not know their creator with certainty that opens the space in them for compassion and, indeed, creativity. A machine can only mimic. A human has that empty space inside (parallel to the vastness of outer space) which allows them to give themselves, to surrender self to “empty space,” and in the moment allow something loving and new to be generated. If “a synthetic” (as David calls himself) should ever attain to that empty space it too could create and truly be equal to its creator.

David cannot or will not dissociate himself from rivalry with his maker. In which case, far from being purely a machine he is in fact a perfect image of the human! A robot-as-rival is a perfect movie image of the human filled up with the other as enemy. He or she is in lock-step with the other, always seeking to emulate and yet outdo. A rival is a robot, fixed mechanically to the being of the other, trying futilely to attain freedom in that last explosive theophany of conquest. This is the satan, the rival who cannot let go, who becomes a robot of desire, and will go down in flames rather than do so.

David is probably the best screen Satan ever. His is the “alien covenant,” one of rivalry and violence, the one that will engulf the world in destruction unless we learn the empty space of forgiveness and love. If you’re in any way involved in teaching Christians about the meaning of their scripture, bring them to see and understand this movie!

(P.S. In the prequel, Prometheus, the main protagonist, Dr. Elizabeth Shaw, wore a cross around her neck, as a sign of overarching faith, something resented by David. In Alien: Covenant the main female protagonist, Daniels Branson, wears an iron nail on a leather band around her neck. It has an ordinary meaning–she wants to build a log cabin on the new planet–but the contrast with Prometheus is unmistakable. Is the iron nail of Alien: Covenant the rivalry and violence that crucified Jesus? In the imaginal universe of movies it does not matter if a particular trope is fully intended by the director or not: the answer here has to be “Yes!” In the theological logic of these two movies a 21st century version of the work of the cross is becoming more and more difficult to miss.)