(Spoiler alert: plot themes and details discussed.)

If you’re looking for religious uplift don’t go to see Ridley Scott’s Exodus, Gods and Kings. If on the other hand you want an anthropological reading it really is a five-star movie.

If you’re looking for religious uplift don’t go to see Ridley Scott’s Exodus, Gods and Kings. If on the other hand you want an anthropological reading it really is a five-star movie.

About halfway through, the Pharaoh, Ramesses II, speaks these words to Moses: “What is your god, a killer of children? What kind of fanatics would worship a god like that?” Ramesses is no slouch at killing himself, but in his words there is the genuine sense of outrage that any civilized Westerner must share at the killing of the firstborn.

Once again a film-maker returns to a biblical scene to worry the pleated skirts of the central Western story. What really was going on? What was important? What images can be distilled so that we may perhaps find ourselves with a different perspective leaving the cinema?

Scott and the screen-writers have a certain vision right from the outset. It is about violence and its mimetic essence–although a concept like that is of never mentioned.

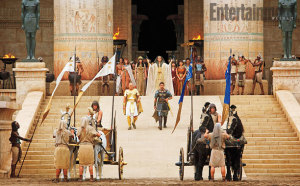

![MV5BMTc2MjQwMzI2NV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTQzNjUxMjE@._V1._CR41,12,2916,1943_SY100_CR25,0,100,100_AL_[1]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/MV5BMTc2MjQwMzI2NV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTQzNjUxMjE@._V1._CR411229161943_SY100_CR250100100_AL_1.jpg) Near the beginning Seti I, the old Pharaoh, gives the two “brothers,” Ramesses and Moses, fabulous gold-inlaid swords inscribed with their names. For a moment they believe they have been given the wrong swords, each with the wrong name. But Seti insists: you have the sword with the other’s name in order that “you might take care of each other.” Despite the fatherly solicitude we sense that the truth is rather the inverse. At once the theme of mimetic doubles intrudes, a theme that is absolutely biblical. The “brother” is so close to me, and so much my rival, he takes away “my identity,” my standing, my inheritance, and the outcome is a simmering mirroring violence.

Near the beginning Seti I, the old Pharaoh, gives the two “brothers,” Ramesses and Moses, fabulous gold-inlaid swords inscribed with their names. For a moment they believe they have been given the wrong swords, each with the wrong name. But Seti insists: you have the sword with the other’s name in order that “you might take care of each other.” Despite the fatherly solicitude we sense that the truth is rather the inverse. At once the theme of mimetic doubles intrudes, a theme that is absolutely biblical. The “brother” is so close to me, and so much my rival, he takes away “my identity,” my standing, my inheritance, and the outcome is a simmering mirroring violence.

But the rivalry between brothers is just a foil for something far bigger, something that seems to be the real rivalry–that between Pharaoh and the God of the Exodus. In a brilliant stroke of theatre the figure of God is cast as a ten-year-old, a spiteful, narcissistic boy. The only thing that stops him officially being a sociopath is that he is a child–one badly in need of parenting!

God directs Moses back to Egypt to set his people free, and Moses sets out in conventional fashion, beginning a guerilla war attacking Egypt’s food supplies. He says it is a “war of attrition” and will take many years. God tells Moses that he’s wasting time and instead he should just step back and watch what He can do! By introducing the motif of a guerilla war–not in the bible–Scott suggests that this is in fact the nature of the plagues: a guerilla campaign. God mimics Moses’ war, simply doing it much better. In other words, the God of the Exodus imitates human violence.

In a way this a fairly banal point until you get to the slaughter of the firstborn. The naturalistic sequence of crocodiles attacking en masse, spilling blood in the water, followed by frogs, flies, boils, death of cattle, hail, locusts, darkness, all seems par for the course: if control of the natural environment is God’s purview then this “step aside and see what I can do” seems fairly reasonable. It is when God overhears Pharaoh talking to himself and planning to drown all the Hebrew children, and then resolves to act first that it gets truly nasty. As Stalin famously said, “When a million die it’s a statistic; a single death is a tragedy,” and throughout the movie we have been cued to feel empathy for Pharaoh’s infant son due to his evident love for the child. When the Angel of Death passes over and the baby stops breathing from one moment to the next, it is then that we feel how truly horrifying mimetic violence is. And it is God doing it!

The following scene reinforces the point. Pharaoh carrying his dead baby faces Moses now become strong and saying “None of the Hebrew children died.” The roles are reversed. Moses and his God are now the conquerors and Pharaoh tells him and the Hebrews to leave Egypt, to go, get out of here…. But then God–or mimetic violence–“hardens Pharaoh’s heart” once more. And he decides to chase down the Hebrews with his chariots, providing the supremely cinematic climax. This time, however, it does not seem heroic, not at all Charlton Heston’s pious parting of the seas. It feels sick-making, as if we’ve seen all too much violence, and the tidal waters of the Red Sea returning on Pharaoh’s army cannot wash that feeling away. ![exodus_4-1[1]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/exodus_4-11-300x123.jpg)

Something has happened between Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 telling of the story, The Ten Commandments, and now. The confident moralism, the mythic divine violence, the majestic maleness, this has been replaced by spite, fanaticism, revenge. Actually the imperial state, in the figure of Pharaoh, is prepared to kill children, and God in his guerilla-terrorist tactics simply seeks to outdo the state at its own game. There is not a whisker to choose between them. To have this so clearly presented on screen is a crisis both for the state and religion.

Tony Bartlett