Is there a way of talking about our human world today that does not descend rapidly into apocalyptic nightmare, or, alternatively, escape into a religious realm with the promise of a heavenly otherworld to be enjoyed after all this is over?

This question struck me forcibly at a recent conference in Paris that came together on the hundredth anniversary of the birth of René Girard. Girard is famous for discovering human mimesis, the insight that people copy each other preconsciously, and especially in the area of desire. When we understand this, we easily see how wars arise and escalate, and at the conference this was underlined. Just like rival individuals, each political power imitates the other in their desire, their demands, and the fury of their military response. Add the fact that each warring party has nukes and we’re on the very brink of apocalypse. Or, what is called “apocalypse.”

The problem is that the biblical book that gives us this term (the last book of the bible) actually means by it “revelation,” a drawing back of the veil. And part of the revelation (the apocalypse)—along with the violence—is the nonviolent Lamb, a figure which presides over the whole book and in the end gains final wonderful victory on earth.

How does this happen? Is it purely supernatural? Some form of scriptural magic? (In which case, open to serious doubt as a fanciful fairy story.) Or, is there some kind of real and rooted human process than can and will bring this end about?

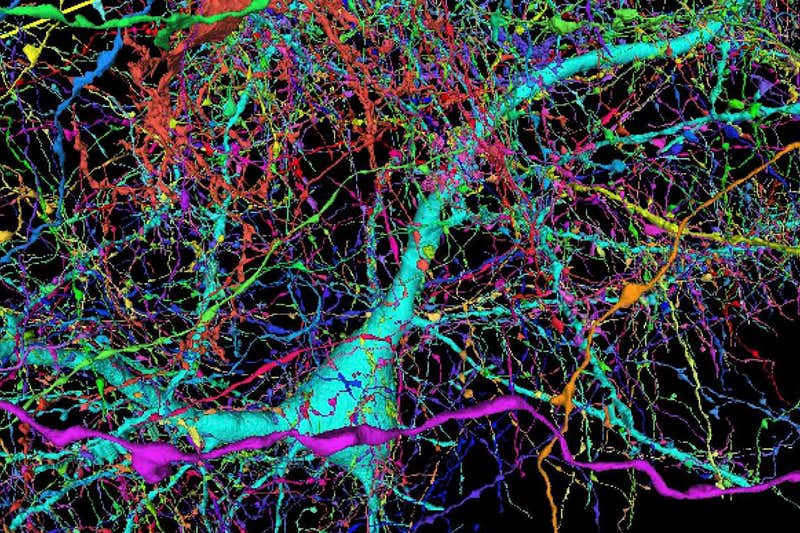

When people come together at a conference like the one in Paris there are a lot of thoughts and ideas whirling around, and things can often be seen in startling new ways. One of Girard’s original concepts was what he called the “interdividual,” meaning that human beings are not solitary psyches, but actually an open-ended system of interaction and agency with others. A psychologist working with these ideas came up with the happy expression “the self between.” The self is not a godlike pure consciousness, but a mutual product together with others with whom they are in relation. Humanity is always a dense interwoven system of possible and actual connections with others. This “self between” was mentioned at the conference, and it implies that any of us, any “self,” will always and necessarily be in constant interchange with others to achieve our very identity and being in the world.

Another of the concepts at the conference came from Benoit Chantre, the most important of Girard’s collaborators in the final period of his career. Chantre suggested to Girard the idea of “intimate mediation,” something which Girard accepted. This needs a bit of explanation. An original distinction made by Girard was between what he called “external” and “internal” mediation. Essentially this means we all choose models in our lives. A model that truly has our admiration, respect, and honor exercises “external mediation.” Such a model shows us elements of conduct and behavior that we seek to copy, but we never enter into competition with that model. “Internal mediation,” on the other hand, refers to a model which becomes our rival, one whose actual way of being in the world we want to possess and have for ourselves. Bob Dylan perhaps said it best: “You’re gonna have to serve somebody . . . it may be the devil, it may be the Lord . . .” In Girardian terms “the Lord” would be somebody you truly honor, while “the devil” is the rival who makes your life hell.

What Chantre added is really dramatic. He points to a third way, a mediation that goes in another direction altogether, not to something outside and above ourselves which keeps order, nor to something inside ourselves which torments us and creates disorder. Rather, there is something that enters into our selves, in the very same “between” space that the rival enters, but with an entirely different dynamic and outcome. Chantre does not explain this in great detail, but he does say explicitly and precisely that the “intimate mediator” is not our rival.

How does this work? The thought that I added at the conference was that intimate mediation was necessarily nonviolent. It cannot enter into our “selves” in the same place as “internal mediation” and not create rivalry unless it is essentially nonviolent. This would then be close to Dylan’s poetic and biblical thought of “the Lord.” In a world of interior mediation (inside the self) every other model can provoke rivalry. Only the supremely nonviolent, nonresisting Lamb can exercise mediation in the self and not provoke us to retaliate.

But this should not at all be understood in a dogmatic religious sense. It is saying something quite different from “everyone should be a Christian.” First, if interdividual psychology is correct then it means that there is always this “space between” human beings. It is a space that has been steadily growing in power in the romantic ages, until now when just about everyone on the planet is involved in some kind of internal relationship. But, at the same time, the figure of the nonresisting Christ has inspired countless imitators, from Stephen of the New Testament, through to Gandhi, Bonhoeffer, MLK Jr, Romero, Mandela, Edith Stein, Rajani Thiranagama etc. These are heroic, boundary figures, but what they represent is a progression of the “space between” to a progressively new depth and human agency. Here people are prepared to give everything without retaliatory violence, in order to bring life for others. All of them relate to this space for personal reasons, with different kinds of stories and probably different levels of clarity. But what is consistent is the opening up of this space, such that it deserves its own name. Because it represents a depth of giving, a surrender to a sea without bottom where the very water is giving for the sake of others, it might be called “the deep between.”

My argument is that this is a real space, one that stands as radical alternative to mimetic rivalry, violence, and war. Many people don’t recognize it, possibly thinking it a kind of idiocy, or, at best, a religious dream. But the whole Girardian scientific logic, through psychologists like Oughourlian, and astute companions and commentators like Chantres, leads necessarily to this. It is in fact a matter of a general human structure, hidden to the light that looks only at rivalry and violence, but just as real as those things, and even more so. It lacks guns, tanks, bombs, planes, generals, and tyrants. But, nevertheless, it leaves an actual and powerful trace in that world. MLK Jr leaves a trace. Edith Stein leaves a trace. And the trace creates further traces, which are signs and structures that enable peace to flourish. Peace and disarmament treaties, commissions on truth and reconciliation, peace activists, artists and artisans, campaigners for the environment and for the ethical treatment of animals, all these things are traces of the deep between. It is vital to bring this human space to prominence, because unless this space is effective and spoken about, the discourse of war and escalation appears inevitable. (Girard’s own word is “implacable.”) On the contrary, there is no apocalyptic doom, because there is an actual alternative human space of nonviolence and peace which is practically effective in human affairs. It seems vital to continue to raise this space to public discourse in order that it might challenge the fatalism of the so-called apocalypse.

A particularly telling example of ”the deep between” I might suggest is the teaching and conduct of a Turkish Islamic leader by the name of Fetullah Gulen. In the nineteen seventies this person founded a movement called “Hizmet” (service) which now comprises several million followers. They work across the world in hospitals, schools, aid projects, media outlets, but they have been subjected to severe persecution in their native Turkey, falsely labelled “terrorists” by a dictatorial regime needing a convenient scapegoat. Gulen is himself in exile in the U.S., constantly under threat from political forces both in Turkey and the U.S. But he consistently teaches nonviolence to his followers. His words that I give below serve to demonstrate that the human space I am talking about does not belong to the religion of Christianity but is arising organically in the world as a transformed way of being human on the planet. Certain spiritual leaders may see it more clearly because they are sensitive to the transformative impact of revelation. But, once again, that does not remove it from the human. On the contrary, this revelation is radically about being human. The following words belong to a discourse that rises up in our time as a tide of human meaning alternative to the violent clichés of “apocalypse.”

Prepare yourself to forgive these people who committed genocide against you. When they come back with a sorry heart, let them find you with an open arm. Do not become a tyrant yourself by responding in kind. You are fighters of love.

![th[6]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/th6.jpg)

![th[6] (2)](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/th6-2-300x187.jpg)

![atom-electrons[1]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/atom-electrons1-300x200.jpg)

![th[8]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/th8-300x187.jpg)

![th[4]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/th4-300x180.jpg)