The proverbial canary is in its cage. Someone opens the door. The pretty bird steps out, looks around, and goes straight back behind bars.

The liberator’s definition of freedom may look like the end of the world to its feathered beneficiary, even if from the outside the caged canary might seem deprived.

On the other hand, if you make a cage big and rich enough and put lots of canaries and other songbirds in there together, suddenly they produce a society and a culture that has its own definition and assertion. Maybe then the cage becomes a problem to everyone around it, because it is using up so many resources to create its gilded lifestyle, and because, incidentally, the birds make a whole lot of noise. Nevertheless and all the same, the cage continues to deny freedom to its captives.

I once visited a community in Latin America where the rooms of all the brothers were set on a gallery around a central courtyard. Someone had the bright idea of building a huge aviary in the courtyard, reaching from the ground to the roof. The birds were certainly pretty, but the first morning I was there I was awakened by this deafening blast of competing birdsong breaking out at 4.20 am, an atrocious kind of alarm-clock. Needless to say, I got away from that house and its hellish chorus at the first possible opportunity.

Is it possible that aspects of the culture and society of North America are comparable to that exaggerated aviary? North America is very large, it has an idiosyncratic sense of freedom, it makes an ear-splitting noise proclaiming it, and yet in certain respects it is still a cage. Stepping outside the aviary seems like catastrophe to many Americans.

American freedom is built upon a gigantic landmass discovered by Europeans at a point when their technological development was taking off, enabling them rapidly to assert control over the territory, its indigenous peoples, and its resources. The wide-open spaces and the relative swiftness of expansion became a sense of freedom, a phenomenon of effortless power, movement and destiny. Allied to Enlightenment values of equality, individual liberty and rights, the experience was intoxicating and defining. Soon, just behind the gun, the cotton gin, the smelting yard and the railway, came the movie camera. Not only did this freedom express itself concretely in the prairies, the mountains, the rivers, it mirrored itself to itself in an endless stream of films, set against the magnificent backdrop and following the relentless movement of humanity across it.

We also have to bear in mind what this movement of humanity was getting away from. Poverty, landlords, oppression, pogroms, all such was left behind with only the new spaces rolling out in front, “from sea to shining sea.” No wonder all the birds in the aviary sung their hearts out!

But the fact remains that this is a unique and specialized society, spiritually and materially walled off from the rest of the planet and, of course, from aspects and sub-sets of its own territory and peoples. Because no matter the crowing of the cocks and hens true freedom still lies beyond the walls of this self-constructed cage.

Concepts of individual liberty come from specific and privileged circumstances like North America and the English bourgeoisie on the crest of industrial growth and great comparative wealth. In contrast the industrial working classes in Britain and France developed a sense of identity over against the rampant individualism of the factory owners, bankers and financiers. Necessarily this was a class identity, involving the whole mass of workers, combining their power against the might of the individual owners and their top-of-the-crop families.

It is this class identity which came to color what is called “socialism,” and now so offends U.S. sensibilities, pitting a brute, ugly collectivism against the ideal beauty of the individual. The ugly “starling” collectivism is what the canaries sing against day after day, trumpeting their unique private beauty to anyone in earshot.

But the truth remains theirs is not private beauty. As underlined, it was attained and is maintained by public means, in a particular time and space, channeling exceptional privilege to the fortunate citizens within its continental boundaries. Meanwhile, there is another version of beauty and freedom which the canaries can hardly conceive, so hostile are they to what they see as the massed ranks of collective unfreedom. This is a freedom outside of their cage which they reject because they feel happier in their five-star confine.

The freedom outside the cage is created by the power of compassion. To share the life of every other creature in the world, by means of the emotion that makes us one with them even in their suffering, this is to open an endless breadth of human relation. If freedom is the sense of movement and the possibility of engaging it anytime anywhere, then the freedom of compassionate relation is infinite, while the defense of privilege is a cage. The recent politicization over Covid safety demonstrates much of what is at stake. In a recent op-ed in the New York Times Charlie Warzel compared the furor over mandated masks to the politics surrounding gun rights and the human consequences that flow from them.

“As in the gun control debate, public opinion, public health and the public good seem poised to lose out to a select set of personal freedoms. But it’s a child’s two-dimensional view of freedom — one where any suggestion of collective duty and responsibility for others become the chains of tyranny.”

Warzel goes on to say, “In this narrow worldview, freedom has a price, in the form of an “acceptable” number of human lives lost. It’s a price that will be calculated and then set by a select few. The rest of us merely pay it.” This may seem a harsh judgment but explained as the canaries’ addiction to their aviary it makes full sense. Warzel’s assessment was underlined by an editorial piece in the same newspaper on Aug 6, reporting America’s “unique failure” to get the pandemic under national control. “First, the United States has a tradition of prioritizing individualism over government restrictions. That aversion to collective action helped lead to inadequate state lockdowns and inconsistent adherence to mask wearing based on partisanship instead of public health.”

As in gun rights the public health failure of Covid response is not an unfathomable mystery. Guns belong to the technology by which mastery over the Americas was asserted. In the hands of individuals, it provides the cumulative power of a king and army, expressed in a single trigger burst. It provides the individual with the rule of a monarch over an alien and hostile world. L’etat c’est moi! In comparison, Covid is a tiny virus, something which reverses the perspective but maintains the metaphor. Now the power is a minute pathogen set against the Leviathan of the individual. Thus, “It shall not pass,” not because of a humble, other-conscious mask, but purely by royal decree!

What is unique about humans is their limitless power of relation. As Rene Girard has shown us, this can result in unending rivalry, the source of wars and killing. Or, the very same mimetic connection can bring community, compassion and love. In the past this relation has been called “socialism” but there is an inherited element of class conflict in that political tradition, one that makes the canaries sing all the louder in opposition. Compassion, instead, invites everyone into a more deeply human life, one without violence. Indeed, if humans are to survive at all on earth then compassion must become a necessary way of life, rather than an occasional fit of sentiment. Compassion then might be called a “new socialism,” if by that we mean the compassionate elements clearly present in the old tradition now come front and center in a mode of positive human transformation. The current cultural crisis in response to Covid (and, afterward, to its aftermath) throws up the possibility of seeing everything from a revolutionary new angle. Many Americans already share a great sense of compassion. It is simply a matter of making this a human and political virtue in its own right.

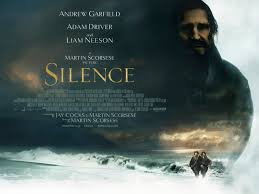

This is a hugely different question and it is at this level that the repeated images of Christ–unfailingly nonretaliatory and nonviolent–transcend the eponymous silence of God. Indeed, the test of apostasy is to trample on an image of Christ and this gives Scorsese endless occasions throughout the movie to render a powerful semiotics of the nonretaliation of the Christ. Jesus again and again has a foot planted on his face and not once is there a glimmer of revenge.

This is a hugely different question and it is at this level that the repeated images of Christ–unfailingly nonretaliatory and nonviolent–transcend the eponymous silence of God. Indeed, the test of apostasy is to trample on an image of Christ and this gives Scorsese endless occasions throughout the movie to render a powerful semiotics of the nonretaliation of the Christ. Jesus again and again has a foot planted on his face and not once is there a glimmer of revenge.

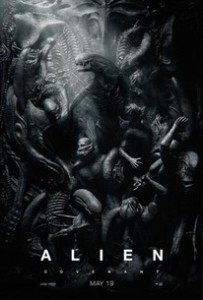

A sense of spectacle as spectacle undergirds both movies, a conscious meta-awareness of what exactly it is we are waiting for and watching when we watch.

A sense of spectacle as spectacle undergirds both movies, a conscious meta-awareness of what exactly it is we are waiting for and watching when we watch. I have called moments like this in other movies “

I have called moments like this in other movies “

![MV5BMTc2MjQwMzI2NV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTQzNjUxMjE@._V1._CR41,12,2916,1943_SY100_CR25,0,100,100_AL_[1]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/MV5BMTc2MjQwMzI2NV5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTgwMTQzNjUxMjE@._V1._CR411229161943_SY100_CR250100100_AL_1.jpg)

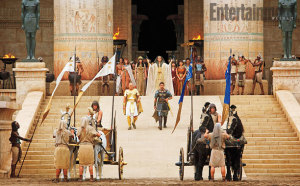

![exodus_4-1[1]](http://hopeintime.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/exodus_4-11-300x123.jpg)