GRAVITY OR GLORY

(Warning: some plot theme spoilers.)

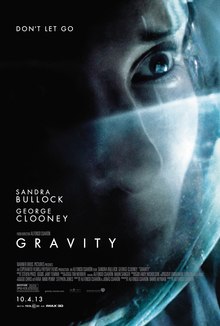

The release of Christopher Nolan’s space epic, Interstellar, prompts immediate comparisons with last year’s orbital movie hit, Gravity, and for several reasons.

There is the suffused religious tone of both films, pitching audiences headfirst into the cathedral geometries of outer space. Gravity also plays a key role in each storyline.

In the case of the eponymous feature almost the whole thing consists of the accelerating effects of gravitational force, as the spinning earth pulls matter around it or toward it in a constant terrifying plunge. In Interstellar gravity acts as some kind of unifying field allowing improbable “ghostly” communications across the galaxy.

In addition a family team wrote the story and screenplay for each of the films: father and son, Alfonso and Jonas Cuarón, in the case of Gravity, and two brothers, Christopher and Jonathan, in the case of Interstellar. It seems that blood relationship allows the trust and shared imagination for these cosmic explorations.

There is certainly a trend. Space allows for visual hints of a great Other hidden somewhere in those trackless spaces and possibly in relationship to us. Is there not a person or persons watching us unseen from the depths of this dark cosmos? In Gravity two of the spacecraft entered in the course of the action have religious icons, a Buddha in the Chinese space-station, and an Orthodox Virgin and Jesus in the Russian module. In Interstellar the space-mission is named “Lazarus”, using the gospel story as metaphor for the possibility of finding a new planet to sustain life when the present one is dying.

But right there is the rub, a vast difference between the two movies. In Gravity everything pulls you back to earth. When the female astronaut, Stone, acted by Sandra Bullock somehow survives her fiery re-entry and emerges from her module into a shallow lake and then onto land she grasps a handful of mud and mouths “Thank you.” The earth here is our home, filled with life and hope. Nothing in that vast blackness up there could compare to it.

In contrast, in Interstellar, the earth is cooked, fried, a roiling dustbowl of failed crops and certain starvation. Our only hope is to begin again somewhere else, in some alternative planet reached via quantum anomalies which somehow appear in our solar system. You could say the first movie is Hebrew biblical: God created the earth as good and did not intend it to be a waste (Genesis and Isaiah). The second is Gnostic and Greek: our destiny is always away from here, up in the sky, guided by beings who belong on a supernal plane far beyond.

These are alternatives with a two thousand year pedigree. And along with them goes a parallel division, although not quite so marked. The transformation of the earth requires a theology of the cross, it requires self-giving. In Gravity the male astronaut, Kowalski, has to let go of his life in order that Stone might survive and return to earth. In Interstellar Cooper, the lead astronaut acted by Matthew McConaughey, has to take an enormous risk but in true hero fashion he ultimately survives and finds glory.

This underlines the difference. We can only remain on earth with our seven billion brothers and sisters if we’re prepared to surrender some things. Otherwise it could be the way of Nolan and the Gnostics, with a few hundred thousand of us floating gloriously somewhere else in space.